Credits: Der Mord - Public Domain

The sage of Boullay

So many loose threads - but which one do you start to pull? The novel »The Crimes of My Friends« doesn't make it easy. Starting with the question of why Georges Simenon used the word »friends« in the title, through »Nanesse « to the central character Hyacinthe Danse. Then there is the comparison of reality and fantasy.

In the German-speaking part of Belgium, until the 1940s, there was a newspaper with the quaint name »Fliegende Taube« (Flying Dove). Naturally, I was absolutely enchanted by the title of the publication, which appeared twice a week. For a serious publication – beyond pigeon breeding and the sport of racing pigeons – no one would choose such a name today. Marketing would already be questioning: »And how do we convey this on social media?« before anything else.

Back then, it was possible, and here is where we should begin our journey into the depths of Hyacinthe Danse. Under the headline »Jesuit Priest Murdered in Liège,« the act of a madman is described. The article consistently makes these assessments. Here are a few phrases that reflect the sentiment in the article:

- »It is likely to be an act of madness.«

- »The court believes it is dealing with a madman.«

- »It seems to be the crime of a madman.«

The lead story in the article had been about the dead priest in Liège, but as it turned out, Danse had not only killed his and Simenon's former confessor but also his mother and his ex-girlfriend – the latter not in Liège but in Boullay-les-Troux.

Let's go back to the beginning of the story, just as Simenon did in his novel.

Hyacinthe Danse

Credits: Public Domain

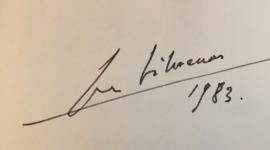

Hyacinthe Danse murdered his lover and his mother on May 10, 1933. But what was the real beginning of this crime? Was it when he published the first issue of his magazine »La Nanesse« in Liège, of which I, despite being not even 17 years old, had become a co-founder due to an improbable coincidence?

Readers of the German translation might be misled here. The paragraph could suggest that Danse, along with Simenon, founded the magazine and then published its first issue. That was not the case, and Simenon's further descriptions do not suggest so either.

The newspaper was founded by another individual who is introduced in the next paragraph of the novel: Ferdinand Deblauwe. He, as can be read in the novel (or the linked article), would also not remain an unnoted figure in the annals of criminal history.

»La Nanesse«

Deblauwe is described by Simenon as a journalist who was well-established in Liège at the time of the founding of »La Nanesse«. The man was significantly older than Simenon, who was about sixteen years old at that time, and worked for a Liège newspaper. The elder looked down on the younger with a certain condescension, while the latter responded with admiration for the man's demeanor and style.

On one hand, Simenon was part of a cool clique known as »Caque« (»Herring Barrel«) – where they partied, drank, and discussed everything in the world in a lofty manner. The catch: everyone outside of this bubble found it silly and couldn’t recognize its value. This included Simenon's mother – which was only natural and showed how elitist this little group appeared in the eyes of the young people; but it also included Deblauwe – who, however, was an idol for the young man himself, which made his disdainful assessment of the group hurt all the more.

According to Simenon's account, it was Deblauwe who approached Simenon to hire him as the editor-in-chief of the journal. The temptation was great, a good price per line was paid, and since it was supposed to be a sort of satirical paper – four pages in length – it wasn’t about fact-checking. As a young journalist roaming the city for his main job, so much caught his eye that he had endless ideas for editorials. The position of boss had a minor flaw: he was the only writer and responsible for all the texts. So, he was primarily his own boss.

According to the novel, the financier was a Romanian who had married a young woman from Liège's high society. The family tried to get rid of him after they realized what a rascal he was. The unwelcome husband retaliated with the newspaper, placing articles intended to damage the family's reputation.

Liège has a tradition of puppet theater that is still highly regarded today. Simenon wrote in his novel that it was customary to go to the puppet theater on Christmas Eve. In the performances, one encounters a clever, strict, and somewhat jealous character known for good cooking skills. She was the only character who could talk back to and physically challenge another main character – Tschantchès. Some sources describe this character as quarrelsome. She was and is known as »Nanesse«. After other names for the future paper were discarded, this one stuck.

While Simenon was thrilled about the job not only because of the income, after reading the first issue, his mother told him that she thought nothing of his outpourings in the publication. The financial support for the journalistic startup by the Romanian soon dried up.

Simenon does not detail the true reasons why he decided to quit »La Nanesse«. According to him, he left after the third issue. He justified his departure to his senior partner by saying that his director at the »Gazette de Liège« had explained that he could not work for both publications at the same time.

His successor was none other than Hyacinthe Danse.

Two aspects deserve to be mentioned. Upon reading, readers might get the impression that Deblauwe could have been a renowned journalist in Liège. In my opinion, this is due to the youthful glorification that Simenon granted the reporter. If one looks through old newspapers, references to him are only found in relation to the crime he committed and in the affair around Danse. The reason might be that Deblauwe was in charge of the »Accidents and Crimes« section in his newspaper. Since the reports were not published on portals as they are today, he had to collect them at the police station – just like Simenon, who was working in the same function. They must have met while waiting for bits and pieces the investigators were willing to throw at them. And so, Deblauwe was not a big name among the city's journalists either.

In »L'Indépendance« of May 22, 1933, the story is described a bit differently: There it is emphasized, explained that »Nanesse« was founded with Romanian money (as far as on Simenon's track), but the founder would have been Danse, who had chosen Deblauwe to be the director of the newspaper. (In another paragraph of this short article, it gets confusing: There, it is stated that a young student from Antwerp had been hired to write for the newspaper. It would be Simenon. Antwerp?)

Other papers, such as »Wallonie«, support Simenon's account: There, it is reported that Danse would have taken over »Nanesse«. The latter also addresses this in his statement during his later trial.

Simenon's perspective is that the newspaper was the scandal sheet par excellence. A look into the archives shows that the other Liège newspapers either ignored these scandals... or they simply did not exist. Perhaps they were not worth mentioning.

In other papers, there were indeed smaller advertisements in which the so-called satirical paper drew attention to itself. Mischievously, some texts were indistinguishable from editorial content in their presentation, but which editorial board would allow such a text to be written?

Every capitalist currently at the top of 25 centimes is obligated to buy the newspaper »Nanesse«, the descendant of Tatène that has just been released. »Nanesse« consists of a series of small masterpieces of fine irony. Richly illustrated, we find in it caricatures of Messieurs Neujean and de Wiart. »Nanesse« is the best-made satirical newspaper in Belgium. Available everywhere.

Whether one would describe this text as subtle? Probably not:

They are some writers. They have decided to shake up the false gods a bit. They pay the tribute that is due, but they criticize, regardless of acquired positions, and if they deserve it, the most prominent personalities of the city; but they do it without malice, with the ironic spirit in which they have become masters. Of whom are you speaking? Of course, of the editors of »Nanesse«, which is sold everywhere in Wallonia for the price of 25 cents.

The price rises over the years to one Belgian franc, while the number of pages varies. In July 1921, a trial of a Dutch consul against the newspaper is reported, but it takes another five years before things heat up again.

During that time, the newspaper becomes a permanent fixture of the press scene and even sponsors individual races at sporting events, just as other newspapers in Liège do.

Things became exciting in March 1926. The publisher and an editor had been reported and charges were to be brought.

The offenses alleged against Danse were of such a nature that they were to be presented to the jury court, and the accusation was sufficiently substantiated to justify this referral. He was to be charged with slander, defamation, and insult through the press, slanders against the gendarmerie of Spa, against the field guardian of Vottem, against a station master, concerning facts that lie within the scope of their official duties. Additionally, there were defamations against various individuals.

By that point, there was no longer any effort made to name the victims; it had become a long list. The intention was to start the trial in May of the same year.

On April 10, news circulated that Hyacinthe Danse had given up his business with the newspaper. »La Nanesse« had a new owner, who also made himself the director and, of course, had nothing to do with the machinations now being accused.

Two months later, an article in »La Meuse« informed readers that press matters were treated differently by the justice system. With privileges, to be precise. Because, unlike "normal" accused, they were not taken into pre-trial detention. They didn't sit in a "cage" in court next to gendarmes but were allowed to sit next to their defenders. However, they were obliged to appear.

And that's exactly what Danse did not do.

The judge issued a decree that Danse must report within ten days. After that, things would become tricky for him: he would be declared a fugitive, his assets seized, and he would lose his civil rights. The trial would take place regardless, and if the jury deemed it justified, the accused would be convicted.

Danse seemingly did not take notice of this announcement.

His former colleague, a sixteen-year-old mechanic at the time, had the nerve to appear. However, he only had to answer for one of the six articles. His boss had written the other contributions. The judge decided that the two proceedings would be separated. For the press representatives, this drained the matter of its appeal – they had anticipated exciting debates, which were absent due to Danse's absence. They would have to wait another eight years for an appearance by Danse to their liking.

In the early afternoon, the young man received his sentence, which was moderate: eight days in prison.

The second part of the trial began at four o'clock on the same day. This was about the guilt of Hyacinthe Danse. The prosecution read the articles and commented on them. The defender seemed not to have made a great impression on the press representatives present, as he was not mentioned at all. The individual sentences would have added up to twenty-five months in prison – the outcome was two years in prison and a hefty fine for the former publisher.

By this time, Hyacinthe Danse was no longer in Belgium.

»Nanesse« epilog

The new directorate of the magazine was already mentioned. In 1926, it was René Dupont, later Paul Capelel is mentioned.

The newspaper continued for a few more years. A small notice in my favorite newspaper, »Fliegende Taube«, makes this clear. It reported that »Nanesse« had acquired "a miserable reputation with insulting and libelous articles against everything honorable and decent." In May 1932, the mayor of Aubel issued a ban on the sale and publication. This was accompanied by the railway company prohibiting the newspaper in station libraries (Who knew such things existed?) and the post office ceasing distribution.

Such an announcement had also come three months earlier from Tournai. There, the mayor had banned distribution for two weeks. Additionally, there was a trial in which the publisher was ordered to pay damages. All plaintiffs were vindicated in this trial.

At least: None of the later directors would become such a headline machine as Danse.

The crimes of Hyacinthe Danse

A malicious entity, which for years almost went unpunished while inflicting immense harm on numerous citizens of Liège, has made a tragic comeback in our city. This is about the jobless Hyacinthe D'Anse, who for a while dominated the chronicles.

Beitrag zum Mord ein der »Illustrierten Kronenzeitung« vom 19. Mai 1933 – bei der Übersetzung gingen wohl einige Fakten flöten ...

Credits: Public Domain

The spelling of the perpetrator's name should not cause confusion. This remains a peculiarity of the day's reporting in »Wallonie«. This variation was not found in other publications. It clarifies that the editors, after learning of the deed, either briefly consulted their records or the colleagues still remembered the professional peer well. Under the motto: "Ah, that guy!"

How could a journalist not remember the man? According to Simenon, Danse had made it a habit during his time in Liège to appear at all sorts of receptions for dignitaries – mostly uninvited – or to participate in the front row of parades and demonstrations, using an armband to give an impression of importance. Appearance had always been important to Hyacinthe Danse. The impression he conveyed. This also included his habit of securing letters of thanks from dignitaries by sending them praises or suggestions of any nature on topics that were unfamiliar to him as a bookseller (and pseudo-journalist). Had he not committed the crimes, the press offenses like the murders, he would probably have been considered an "eccentric"...

The descriptions in Simenon's novel are almost identical to the press reporting. The differences are minuscule. Simenon avoids naming witnesses, focusing instead on Danse. The journalists of the time were known to operate differently.

On Friday, May 12, 1933, a man reported to the court in Liège. He claimed to have shot a man. The prosecutor's office was not prepared for such a case, being very sparsely staffed at the time. The deputy prosecutor present could hardly believe his ears when his visitor confessed that he had just killed a man and had also been murdering in France. From here, we will chronologically detail how the confessing Hyacinthe Danse proceeded.

The terms »friends« and »girlfriend« were used in curious contexts at the time. On one hand, Simenon uses this word for Deblauwe, who actually wanted to betray him, and on the other hand for Danse, who at best had been an acquaintance. For the press, Armande Comtat was also a »girlfriend«, even though Danse sent her to Paris to work in a brothel. From her earnings, he could live well and pursue his obscure hobbies and projects. It's difficult to see any aspect of friendship here.

This »girlfriend« had met another man in Paris and fell in love with him. She told her pimp that their relationship was over and she didn't want to see him anymore.

Apparently, he managed to convince her in a personal conversation to come with him to Boullay-les-Troux, where he lived with his mother in a rented house – along with Armande Comtat, who spent her days off there. This was on May 10th.

His aim was surely to convince her not to leave him. The conversation went awry (or not to his satisfaction) and in the end, she was – according to his first statement – strangled on the floor.

He went downstairs from the upper floor, where the crime had occurred, to the kitchen... where his mother was. He asked her to make him an herbal tea. The mother asked him where Armande was and went upstairs. She must have only briefly seen the other woman's body. Because behind her stood her son, who then killed her with a hammer.

He went to Paris, where he had already stored his luggage at the station, and from there to Brussels. Here, he went to the criminal police to turn himself in, since he still had a two-year prison sentence to serve.

To his disappointment, he found out that his sentence had expired. This was a shock! Because he had assumed that if he was in a Belgian prison, nothing could happen to him in France. Now, he envisioned extradition, a trial, and the guillotine. Danse did not want that.

He sought advice and concluded that only another crime could save his life.

Danse went to Liège and visited the Jesuit priests' nursing home. There, the double murderer asked to speak with his old confessor and teacher, Père Haut. This conversation was granted. The clergyman was very nice and offered a beer. Then Danse pulled out a weapon and shot the old man. He died instantly.

This is the point where we entered the story, and Danse went to court, where he told his story. What puzzled both the investigating judge dealing with the matter and the journalists: At that time in France, no one had noticed that two women had been killed in Boullay-les-Troux. The colleagues had to go and check and saw that it had not been a bad joke.

During the autopsy of the women, the investigators found that both women had their skulls smashed and their throats cut. Danse apparently really wanted to make sure. The forensic examination determined the time of the crime to be between two and three o'clock in the morning.

The sage

In Boullay-les-Troux, Armand Danse, as previously mentioned, had the worst reputation. Besides his brutality towards his mother and his lover, as well as some of the villagers, he was accused of his open disdain for the peasants, his uncompromising and exaggerated political views, and his dubious income. Indeed, hardly any commendable lucrative employments were known, and the residents of Boullay-les-Troux sometimes wondered what he lived on.

During the trial, a more nuanced picture emerged than what has been depicted here. It was a process of deterioration. Danse was initially welcomed warmly and was approachable at the beginning. The Belgian integrated himself into the community.

After settling down, he wrote contributions under twenty pseudonyms that were meant to honor the »Wise Man of Boullay« – himself. These included critical studies on his own works and imaginative writings on transcendental research. He is said to have held spiritist sessions on his property. However, the reporters did not find out with whom these took place. There was a guru who celebrated himself but had no disciples. Good marketing consists of choosing the right names. He named his house »Thebais« and declared it a temple. The combination of a lack of followers and strange rituals led to »Thebais« being considered a haunted house in the town.

Only over time did it become difficult with the man. The question of what he lived on also arose because he was often late with his payments to traders.

He presented himself as a fortune-teller, among other things. He planned to publish a magazine named »Savoir«. For this magazine, Danse had written all the articles himself. The production was well advanced at the time of the crime. In it, as the editor, he provided insights into his extensive knowledge, ranging from graphology and palm reading to astrology, phrenology, and numerology. A reporter dismissively commented on the service offering with the words »Human stupidity knows no bounds!«

In the journalistic public sphere – here as well – Danse did not only appear under his own name but as »Armand Montaigle-Claudel«. Many of his articles and poems are marked as such.

Head off?

Already on Monday after the act, the Belgian newspaper »La Soir« pondered whether the murders in France would be atoned for. The case would be quite simple if it involved a Frenchman. Since the acts in France occurred before the crime in Belgium, the Belgians would deport a Frenchman and foreigner to France. With all the consequences.

In the case of Danse, the matter was different. Although the French would request extradition, since Danse was a Belgian citizen, the government in Brussels would reject such a request. Beautiful in this context is the sentence:

But the situation is quite different since Danse is Belgian. Between civilized nations, extradition in this case is always denied. A country does not extradite its own citizens to another country.

Could someone remind the British, who have an extradition agreement with the United States and do indeed extradite their own citizens – it doesn’t even have to be for murder or manslaughter, as seen in the case of Christopher Tappin?

And since the introduction of the European Arrest Warrant, the situation has also changed within the community: There is an obligation to extradite to other countries in the Union.

The approach at that time was strict, because when asked to a legal scholar »What if?«, he said:

In this case, the French judiciary would not have to consider the Belgian verdict, and Belgium would not have to be upset about the French verdict.

However, this expert added that the question would not arise.

As senseless as the murder of the women had been, an ounce of absurdity was added in the case of the father. Because Danse believed that he had to commit another crime to escape extradition. It was no longer possible to determine afterward whether it was due to misinformation that the murderer received or a misunderstanding. But either way, Danse would have been safe from the death penalty in Belgium. He would not have been extradited.

As quickly as the commotion had arisen, it also subsided just as quickly. A week of reporting on Danse, then it was quiet for a while.

His trial was to start in Liège almost a year and a half later. Plenty of time for Danse to prepare his strategy for the trial.

Curriculum vitae

In the run-up to a trial, there is often a focus on the lives of the accused. The same is true here.

Danse was born on December 21, 1891. Thus, the trial took place just before his 43rd birthday.

His parents, who also lived in Liège, gave their son the name Jacques-Godefroid-Hyacinthe. They themselves owned a shop where alcohol was sold. Like Simenon, he attended the Collège de Saint-Servais. Reporters found out that he was only an average student. Even from that time, he was reported to have a bad reputation, though the reporters did not elaborate on what it was based on. After school, Danse enrolled in university, studied medicine, but did not meet the required performance and dropped out after a year.

Like his parents, he wanted to become a businessman, start a family – the normal path that a »good son« was expected to follow at the time. The marriage was not happy, the couple divorced, and his business did not do well, so he pursued a career as an artist. With his revue numbers, Danse was successful in some »bouis-bouis« (explanation in this article) in the French provinces. It was during this time that he also met Armande Contat, a peripatetic. She became his lover.

In the press, Danse's bookstore played hardly any role. His activity as a bookseller was mentioned sporadically, but no storefront or location where it might have been found is mentioned. Simenon is more concrete in his memories in the novel – he stated that the shop was located on Rue Féronstrée.

In »Le soir« of December 11, 1934, it was reported during the trial coverage that Danse had been successful with his bookstore. »Dernier Heure« added that Danse had sold »obscene« books, which the judge would also refer to.

What did the man live on during his time in France? He again called himself »Claudel«, his stage name when performing as a singer. The fees he received for his performances in the surrounding area and the suburbs of Paris were not sufficient for him. As mentioned before, he was dependent on his girlfriend's income.

At the first crime scene, Danse left a message. It was quoted among others in »Independence Belgique«:

For thirty years I have suffered... For thirteen years I was the victim of my lower instincts... Armande is insane... I p.g. [generally paralyzed – note from the editor], son of a man who went mad at fifty... lost a single daughter at six and a half years old to meningitis...

The examination of the acts and, as a piece of the mosaic, this letter give the impression that Danse was insane. A significant part of the time before the trial was occupied by experts dealing with Danse. However, after their seven-month-long investigation, they concluded that Danse had neither acted in a state of insanity nor was he mentally ill. A journalist pointed out in this context that outsiders would resist the idea that such a crime does not have its cause in an illness. What happened here was evil. But this evil had nothing to do with madness or insanity, according to the doctors – a large part of it was considered premeditated by medical opinion.

Contemporaries attributed to Danse childish vanity and megalomania. This was evidenced, for example, by the fact that Danse posed as a morality police officer during the German occupation of Liège in World War I to conduct »necessary« examinations on ladies. When they caught on to his actions, they took him to court and convicted Danse for these offenses. What did Danse make of this after the war? He portrayed himself as a political convict.

The opening

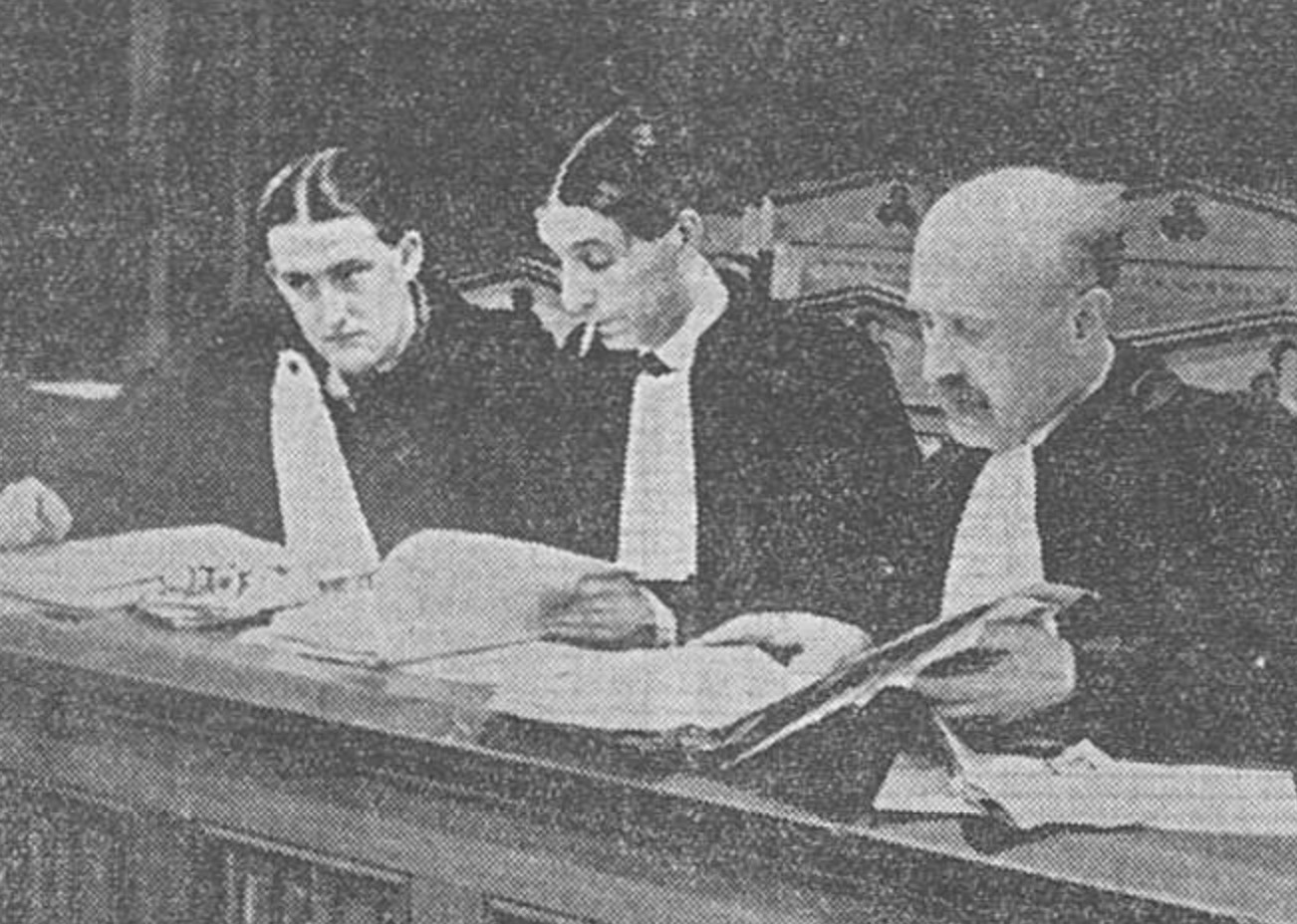

Hyacinthe Danse oben links, darunter links Mâitre Houba und rechts neben ihm sein Pariser Kollege Maurice Garçon.

Credits: Public Domain

The trial against Danse began on Monday, December 10, 1934. For a week, he could enjoy the undivided attention of the Belgian press. Every day there was a lead article on the front page, and the following pages contained more columns discussing the trial in detail.

The presiding judge in this case was Judge Scheurette, and it was tried before a jury.

Court reporters noted that no hall in Liège would have been large enough to accommodate all those interested. The demand was huge, and only a small part could attend the trial. The flamboyant personality of the defendant ensured that quite a bit of excitement was expected for the course of the trial.

Even before the start of the proceedings, Hyacinthe Danse fulfilled this expectation. His defense attorney, Paul Remy, had spent months preparing for the case, only to be dismissed by Danse days before it began. Instead, he hired the Liège lawyer Houba, who had the idea to bring in Parisian lawyer Maurice Garçon. Both had only a day and a half to prepare. Garçon could not participate in the trial for the entire time, as he already had other appointments in Paris that week, and the court was not willing to upheave its schedule due to the defendant's last-minute change.

The man who called himself »the obese« (»l'obèse«), attributed with a weight of 130 kilograms, had lost a significant amount of weight before the trial.

At the opening, Garçon requested a postponement from the court. He and his colleague from Liège had hardly had time to familiarize themselves with the case. Furthermore, he would appreciate it if the court would appoint him as the public defender. The court denied these requests because, for one, it could only appoint a lawyer as a public defender who lived in Liège. Moreover, the last-minute change could not be blamed on the court. The defendant had gone through six defense attorneys in advance – it seemed like a tactic. The responsible prosecutor, Tahon, had also strictly opposed any postponement.

The former public defender, Paul Remy, remained with lawyers Houba and Garçon.

Following this, the interrogation of the defendant began. When asked by the presiding judge how Danse would describe his upbringing by his parents, he said that he had the utmost respect for them. However, his father had been an alcoholic and later went mad. The court president countered that Danse was the only person to make such a claim. All other witnesses questioned in advance had made different statements. The defendant explained that his father did not die from a stroke but from syphilis.

Was it a good way to win over the jurors by telling such things about his father? For those who are now thinking this, it should be assured that Danse did not stop there: His mother was addicted to morphine and megalomaniacal, had a preference for macabre, bloody spectacles like the slaughtering of pigs. Also, for this, as would be mentioned later, there were no further evidences other than the son's statements.

Gerichtspräsident Scheurette

Credits: Public Domain

The conduct of the trial by the court president Scheurette was sovereign, but he did not always give the impression of being impartial. Danse claimed that as a child, he had constantly won prizes, to which the judge pointed out that he had ranked twentieth out of thirty students in school. Shortly thereafter, the judge said to the defendant:

»You are also a vicious and debauched person. You are also a coward because you have never attacked anyone directly.«

Everyone in the courtroom could hold this opinion. A judge should have the strength to keep such judgments to himself at such an early stage – before the verdict of the jury. What Scheurette said was undoubtedly the truth; the appropriate time to say it was not. This was not criticized by the reporters present at the time and did not result in a motion for recusal by the defense.

Danse claimed he had dropped out of his studies because he had shown signs of mental illness. His ex-wife had also stated in the divorce petition that he had had a sexually transmitted disease. It was clear that Danse was focused on only one aspect – he wanted to prove his insanity.

The judge questioned Danse about his bookstore in Liège. He accused Danse of trying to attract German officers with obscene literature. Danse countered that this was not true; he had a church-going clientele. It remained unclear who was interested in the offered licentious literature – after all, Danse did not deny that he made money from the smut. The Germans only bought stamps from him. (A completely different topic, but: Wasn't there something like field post in the German army?)

Next, there was to be an outburst from the defendant. Scheurette questioned Danse about the "La Nanesse" complex: If I understand correctly, Danse had bought the newspaper for 2,000 francs from Deblauwe. At that time, the circulation had been 2,000 copies. By the end of his »reign«" the circulation number had reached 42,000 copies. The judge claimed that Danse had turned the publication into an instrument of extortion during that time. Scheurette was wrong, extortion had been the purpose since its founding... and the defendant was not the founder. But Danse did not retreat to this aspect in his defense; instead, he yelled that it wasn't true and he was not an extortionist. He was still waiting for that to be proven. The judge replied that there had indeed been a trial, and Danse had been convicted. Only, he had shone by his absence. To stick to the truth, extortion had not been charged in the then »Nanette« trial. Otherwise, it would probably have been a criminal court case.

In the pre-trial coverage, it was said that Danse had been the secretary of a priest. During the "La Nanesse" trial, this was mentioned just as little as in the reports after the murders. That day, Danse elaborated on how it came about. He had been approached by the priest in the French town. Danse had been hesitant because he saw himself as an artist, had a lover, and was inclined towards occultism. The priest didn't care, he let the defendant show a sample of his arts, believed that »sins of the flesh are minor sins«, and declared occultism to be nonsense not worth talking about. Thus, Danse was hired by the clergyman and received 2,000 francs per month. One of his tasks: He had to write the sermons.

As good as it sounds, the relationship was not. Danse also stated that the priest had been shabby and had blackmailed him. Actually, the priest was the reason for the triple murder. Later in the day, the defendant claimed that as a fortune teller, he had predicted World War I in 1904 (The president then: »You could have warned the general staff!«) He was the victim of the Mafia and also to blame for the murders.

Following this, the focus shifted to the crimes themselves. During the interrogation, the court president accused Hyacinthe Danse of only returning to Belgium to escape the guillotine:

»The head of the father saves your own head.«

The first day of the trial was evidently quite entertaining.

The experts

On Tuesday, the first witnesses took the stand, and the defendant's statements were unwelcome. The proceedings began with a French forensic pathologist who stated that there were no signs indicating that the two women had resisted.

Following this, Dr. de Block took over, providing insights into the defendant's mental state. De Block attested to Danse's above-average intelligence. His paranoia was feigned, and regarding the crimes, he was completely lucid. According to this expert, there were no signs of insanity. When questioned by his defense attorney, de Block stated unequivocally:

Dans is not crazy, he is neither a persecuted nor a megalomaniac, he is a simulator. He is intelligent and could defend himself.

The discussion with Maître Maurice Garçon dragged on. He tried to persuade the witness to say that there were facets to Danse that would indicate madness. But the doctor was cautious and spoke of not intending to fall into a trap or admit that he was wrong. At this point, Gaçon failed.

The following discussion ensued about the defendant:

Garçon: »Is he aware that he is wrong?«

De Block: »I don't know.«

Garçon: »That's what I was getting at. Danse is wrong, but he doesn't realize it.«

De Block: »Everyone makes interpretative errors every day. That's not an imbalance.«

Garçon: »Even if the errors are systematic?«

De Block: »They are utilitarian.«

Garçon: »They weren't useful when he turned everyone against him.«

Scheurette: »Danse knows he has done something wrong, but he is too proud to admit it.«

After the break, de Block continued. Garçon had no intention of simply dismissing the expert. They discussed what motive Danse might have had for his actions. For the medic, the reasons were clear: Danse had been abandoned by his girlfriend and was materially destitute. After the crime, he faced the death penalty in France – hence the need for the priest to die, to prevent his extradition from Belgium. Clear motives.

The defendant's lawyer asked if there had been an investigation into whether sexual motives could have played a role. Danse might have been a sadist, which would not be normal. Moreover, he might have been obsessed, which could be pathological. Garçon grilled the expert, but it didn't help. The doctor maintained that Danse was not a patient for him as a psychiatrist.

Dr. Leroy, who headed the psychiatric department of the prison in Liège, was also questioned that afternoon. He arrived at the same conclusion as his colleague: Danse was fully responsible for his actions.

Had the defense gained anything on this day? It didn't seem so, even though the Parisian lawyer had put in a good effort.

Witness parade

The following days, it was lawyer Houba's turn to defend the accused. While Garçon had disappeared to Paris, a number of witnesses from the Paris area were present in Liège.

The trial day started with the examining magistrate who initially dealt with the case in Liège. Houba asked if he found Danse unbalanced during this meeting. The witness affirmed, as the murderer was far too calm for what he had just confessed to.

Next, witnesses from Boullay-les-Trous testified. The gendarme mentioned that initially everything was fine – Danse had made a reasonable impression. Later, however, he had to investigate threats against others and also fraud against the accused. Although he had to investigate the affairs, he hadn't had a bad opinion of Danse... probably only until the murders.

The owner of the house where Danse, along with his mother and lover, had lodged, apparently had been glad to find a tenant for her house. The previous tenant had committed suicide. Now, she probably faced the problem that her property had a very bad reputation: a suicide and two murdered individuals. Not good karma. The landlady reported that Danse hadn't been a punctual payer and had annoyed everyone in the village. He hadn't treated his mother well either.

The innkeeper of the village testified that he had thrown Danse out of his restaurant, and the Belgian was an unwelcome guest. And a retired teacher stated that Danse had been normal at first but then had become cheeky and violent. The former official stated that Danse had been dangerous. Asked if he had witnessed the accused being cruel, he replied that he had seen him bite a cat's ear.

The mayor of the village said that the former resident of the village had quarreled with various people one after the other, and these had been people who had warmly welcomed him into the community. Danse himself had tried to blackmail him.

Throughout the day, the fiancé of Armande Comtat and a printer from Limours, who had printed Danses' new publication "Savoir", were questioned. The latter was not supposed to receive any payment for his work.

The French witnesses were followed by witnesses from Belgium – including an examining magistrate, a commissioner from Brussels, where Danse had intended to surrender, a taxi driver, a weapons dealer, and a hotelier.

As a witness, the priest who received Danse at the nursing home of Father Haut and brought him to the old man also testified. He reported on the last moments of the attacked.

Again on this day, there were no witnesses who had anything consistently positive to say about Hyacinthe Danse. If the prosecution intended to cast an unfavorable light on the accused, they had succeeded fully. The prosecutors saved a special treat for last: the testimony of the accused's ex-wife. She had been cheated on by Danse during their marriage. He hadn't cared for the child, despite what he might claim. Danse had also written a justification, verbose but ultimately dangerous – because at the end of the text, there were death threats that prompted the woman to go to the police.

Once again, not a good day for the accused, who allowed himself some prompted escapades and elicited some laughter.

The day of the public prosecutor

The prosecution received reinforcement on the side of the accusation. Father Haut's sister was admitted as a co-plaintiff in the trial and was represented by former Belgian Colonial Minister Paul Tschoffen.

Meanwhile, the defense received only moral support. Other lawyers acting as defenders complained that cooperation with the prosecution in Liège was becoming increasingly difficult and hindering the work of defense representatives by refusing to summon defense witnesses and allowing experts for the defense. This support did not benefit Danse. This issue was raised on this occasion because it was a scandalous trial – and the public would become aware of this cry for help.

The prosecutor argued that Danse was not insane. From the statements, it could be inferred that the former editor did not have a good relationship with cats. He killed the prison cat and reported it in writing to the director. According to the argumentation of the Attorney General Tahon, a "real" madman would have been satisfied with the act. Bragging about it would not have been necessary.

Furthermore, Danse was not suffering from paranoia – his violence was not directed against those he saw as his enemies, but against defenseless people.

At the end of the plea, Tahon stated that Danse had meticulously planned his escape well in advance. This fact alone would indicate premeditation and argue against Danse being insane.

The morning of Mâitre Houba ...

On the fifth day of the trial, Maître Houba was still alone – his colleague from Paris had not yet returned. According to the agenda, it was his turn to present the plea.

He began by casting doubt on the testimonies of the residents of Boullay-les-Troux. For example, how could they see him as a pimp when he had worked as a secretary for the local clergyman? He pointed out that some witnesses reported that Danse had changed over time. Extraordinary difficulties may have led to him not being himself anymore. The defender listed some difficulties: Danse had failed to gather enough advertising for his newspaper. The title of the newspaper was disputed. Furthermore, the village priest had forbidden parishioners from subscribing to the magazine.

Hyacinthe Danse was portrayed by him as an anxious man, and fear had accompanied him throughout his life. Many of his behaviors could be understood in this light.

Then Houba asked why so much importance was placed on what scientists say – it was almost like a religion. Shortly thereafter, he was restrained by the presiding judge, as the defense wanted to draw comparisons with other trials (specifically, the Leipzig Reichstag fire trial), which the chairman did not see as legitimate, even if it were a trial in Germany.

Houba pleaded for the insanity defense for Hyacinthe Danse.

... and the prosecutor's demand for punishment

After the defense attorney, the prosecutor became active once again. He argued against Danse being committed to a care facility. His concern was that in such a facility, Danse would come before an examination commission every few months and could quickly be released if no illness was found.

Danse was a serial offender, and it was unknown who would be next on his list.

The prosecution argued for the death penalty.

Tahon stated that this punishment would only be symbolic. A person sentenced to death would not be executed in Belgium but would be imprisoned for life. If it turned out that he was insane, he could still be treated.

Furthermore, and this was truly an interesting argument: The prisons in Belgium were comfortable. There were many people who hadn't killed anyone but were nowhere near as well accommodated and cared for as criminals like Danse.

The last day

As on previous days, the courtroom was packed. The interest was enormous. Maurice Garçon filed new motions to prove insanity. However, it is not apparent from the further course of the trial that these were followed.

Paul Tschoffen – Anwalt der Nebenklage

Credits: Public Domain

The floor was then given to the lawyer of the co-plaintiff. Maître Paul Tschoffen showed respect to his counterpart at the defense bench, but stated that Garçon had already lost. The great talent of the Parisian would not help anymore. The lawyer argued regarding Danse and his mental state:

»Furthermore, Danse is the only one claiming he's crazy. The examining magistrate and the experts claim the opposite. Danse doesn't realize that the madman is the last one to notice his madness, and he argues to prove that he's insane.«

He addressed the presentation by lawyer Houba from the previous day, in which he stated that he trusted science and the experts. They were honest people who knew more about the subject than he did.

Tschoffen opposed searching for motives in the heinousness of a crime to exonerate the perpetrator. It wasn't about the motives of the crime, he argued, because one couldn't always delve into the reasons for moral depravity. He pleaded with the jury to find the defendant guilty and not let him get away with insanity.

Following the co-plaintiff's remarks, Maurice Garçon spoke. He noted that it was unusual for the family of a priest to act as a co-plaintiff – and this at the end of the trial. Tschoffen had argued that society must be protected. Garçon raised the question of which criminal, in their right mind, would commit the same crimes again. Garçon's argument is not compelling, as according to this logic, there would be no professional or serial criminals. However, reality then as now shows different patterns.

Perhaps the opposing party wanted to point out this slip-up, but Garçon preempted him and said:

»I haven't interrupted you, not even during your most improbable delusions!«

In the remainder of the plea, every aspect of Danse's life was examined by the lawyer for signs of insanity. That Garçon found madness in each aspect shouldn't come as a surprise.

Tschoffe, as the co-plaintiff's lawyer, was once again targeted, as the former minister had worked on introducing a law in the Belgian Senate aimed at protecting mentally ill individuals from conviction.

When the lawyer mentioned the death penalty, he was reminded by the judge that he couldn't discuss the punishment before the verdict – as per the criminal procedure code. The reminder was likely valid, and Garçon did not object, although it was surprising given that the prosecutor from the previous day had spoken very explicitly about his demand for the death penalty.

Garçon, like his colleague Houba the day before, demanded that the defendant be declared legally insane.

The verdict

On that day, shortly before half past twelve, the jury retired for deliberations. They were given seventeen questions to decide upon.

It took them barely an hour and a half to finish their deliberations, and Hyacinthe Danse had to hear that the jurors did not consider him insane.

Danse was described as stunned, but he knew what was coming: both the prosecution and the co-plaintiff argued for the death penalty. Strangely, it is said that even the defense joined in the demand.

With such unanimity, it is no surprise that after a fifteen-minute absence, the judges returned to the courtroom to announce the sentence. He received the death penalty for the murder of Armande Comtat, his mother, and his former teacher, Père Haut.

Diving into oblivion

After the jurors found Danse guilty and the judges had set the punishment, the convicted man disappeared from the public eye. Introverted individuals lose their freedom through such a verdict. People like Danse, however, lose their stage, and what was gathered shows how important it was to him. He had his last grand performance in the courtroom.

The ongoing appeal proceedings no longer offered him this opportunity for a performance. At best, the lawyers would face off against each other, unless it was decided based on files and written submissions.

The era of major reports about him was over.

In the prison of Liège, Danse awaited the outcome of his appeal. After just four weeks, he had distanced himself from some of his views. Nonetheless, the former publisher persisted in claiming to be insane and unbalanced. His malice seemed unchanged, although he had now become calmer and it was reported that he went to communion daily.

His lawyers were concerned because Danse was given sedatives that gave him nightmares. It was also alleged that this made him more resentful towards the prison staff. It was unclear whether he himself was contemplating the possible rejection of his appeal or whether this was mainly preoccupying his lawyers. The suspicion arose that Danse was already resigned to the rejection of his appeal.

In an article in the newspaper »Independance« from January 1935, a possible future for the criminal was outlined:

If Danse were to adapt and show gentleness, he could soon be transferred to the »Literati« department at the prison of Leuven, where he might contribute to the newspaper »L'effort vers le bien« written by prisoners. In this environment, prisoners are expected to demonstrate humility and selflessness.

The appeal was not granted.

On August 4, the »Wiener Tag« reported on the death sentence against Danse and its political implications. The correspondent stated that the defense had submitted several petitions for clemency to King Leopold III, who refused to grant mercy. It was assumed that the death sentence had been signed and was about to be carried out. The »Gazette«, a Brussels newspaper mentioned by the correspondent, cannot be found in Belgian archives. In the Parisian »Matin«, there was a reference to a report in the «Gazette« at the end of July, discussing tensions within the Belgian government due to the royal decision. An interview with the government official mentioned in the »Gazette« did not confirm these tensions when speaking to the French newspaper. Other Belgian newspapers made no mention of the alleged discord.

Instead, on August 7, 1935, under a report that King Leopold had gifted an Opaki from the Antwerp Zoo to the Prince of Wales, the »Fliegende Taube« reported that the king had commuted Hyacinthe Danse's sentence to life imprisonment with forced labor. Other newspapers had reported on the commutation as early as August 1 and indicated that the king had signed it on July 26, even before the reports were published.

The prosecutor had acted as if it were certain that the death penalty would not be executed. However, there was no certainty. Ultimately, the king could have made a different decision – as was the case during World War I. And after World War II, there was a true wave of executions. The last execution in mainland Belgium occurred in 1949, and in the Belgian colonies in 1962. The abolition, removing it from the legal code, didn't happen until 1996.

Danse was a vile character, but he certainly wasn't the worst of all Belgians. After him, there were equally despicable individuals, if not worse. According to a report from 1946, he shared the prison in Leuven with a man who traded in human flesh and another who had skinned his girlfriend. However, Hyacinthe Danse was still the subject of the report.

The reporter from »La Meuse« had visited the prison and also »met« the triple murderer.

Danse, who was well advised, saved his life. Today, he portrays himself as an intellectual in his cell and refuses to work. Sometimes, he addresses his grievances to the prosecutor or even to the Minister of Justice.

For journalists, at least, the topic was concluded. There are no reports of the criminal being released or passing away.

Simenon ensured that his deeds would not be forgotten with his novel.

Simenon in the middle?

Simenon's literary work was not only closely observed by his mother in Liège. Journalists also took notice of what Simenon was producing. Otherwise, the introduction reporting on the murders in France cannot be explained. In the »Wallonie« newspaper dated May 15, 1933, it was stated.

»The Crimes of the Obese«, Georges Sim might have titled this hallucinatory tragedy, which today fills all the newspapers in Europe.

That was a very interesting connection made there. Simenon himself was mentioned in a contribution, as previously mentioned, where it was stated that he knew both Deblauwe and Danse. About the story that unfolded, it was said:

By the way, he went on to excel in his career by writing many crime novels. He is the first to smile about this collaboration between two rascals, both of whom were to become murderers. His name is Georges Simenon. I bet he never could have imagined such a plot for one of his peculiar novels.

Whether Simenon could have imagined that is very unlikely. But he made a novel out of it. He remained very close to the truth regarding the trials against his acquaintances. Autobiographical aspects found in this novel can also be found in other writings by Simenon.

So, the question remains: What is actually still fiction, thus not corresponding to the facts?

I still hear Danse's pounding voice in the courtroom of the Liège Assize Court [...]

Does that mean Simenon participated in the trial? Apparently not as a reporter for a newspaper, as there is no known report by him about the trial. Would he have bothered to travel to Liège as a private individual to attend the trial? That's entirely possible, but with Deblauwe, where he had the opportunity, he chose not to. The reason for this story goes:

I could have attended, but I knew that Deblauwe was risking his neck, and I didn't want to risk confusing him or robbing him of even an ounce of his cold-bloodedness by my presence.

If he was present at the trial against Danse, then he didn't have that concern.

Anyone who studies the descriptions in the press from that time can see that there was a huge rush to the trial. People tried by all means to secure a place and waited in crowds outside the courtroom. How did Simenon manage to participate in the trial without accreditation as a press representative?

And even more interestingly: Wouldn't it have been worth reporting for his colleagues if they had seen their former colleague, who had gained some notoriety through his literary work and glamorous life, and who had connections to Hyacinthe Danse, at the trial? However, such reports did not exist.

So it is assumed that Simenon extensively studied the press to write this novel. Other traces that he was present at the sensational trial in Liège have not been found by me so far.

Secondary utilization

Upon studying all the reports from newspapers of that time, I couldn't help but think: Somehow, this is a story by Simenon. Not the one he wrote in »The Crimes of My Friends«. The writer had left us another narrative in which he addressed the subject.

In »The Death Penalty«, the story revolves around a man whom Maigret suspected of committing murder in France. However, Maigret couldn't prove it, and therefore couldn't prevent the young man from fleeing to Belgium. The intention was clear: Once in Belgium, the man would be safe from the death penalty.

However, Maigret wanted to ensure that the murderer didn't escape punishment.

One thing can save him from the guillotine, the same thing that once saved the murderer Danse from it. If he commits a new murder before being extradited, he will fall under Belgian jurisdiction, which no longer knows the scaffold but will instead sentence him to life in prison.

There he was again, our Danse. And the small misconception, which Danse himself fell victim to: Belgium did not extradite its citizens, regardless of whether they had committed murder or not. If they committed murder abroad, the crime would be tried in Belgian courts. Just like Hyacinthe Danse's murders of his mother and Armande Comtat.